Author: Aparajita Vaid, Moitrayee Das

A decade ago, mental health issues became a household phenomenon in India. Everyone I knew had a doctor on call. Now, a new question arises: Is actively seeking medical attention even without a diagnosed problem the next progressive step? Is Preventive Psychology the New Frontier?

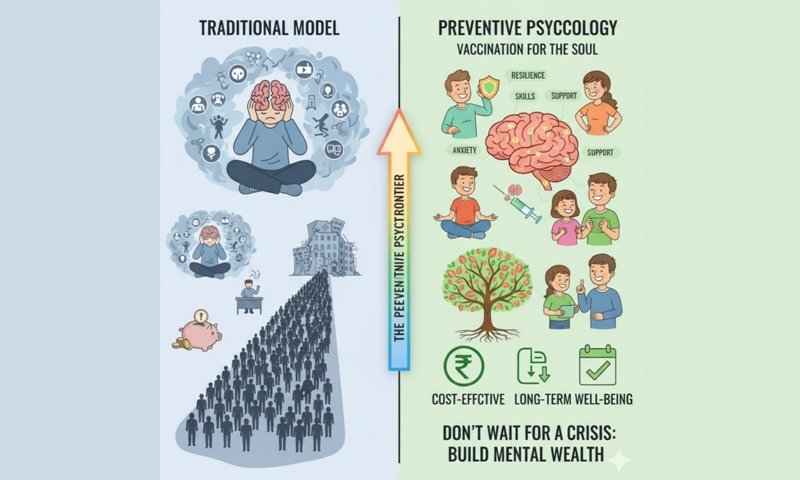

Preventive psychology refers to the identification of risk factors mental health Concerns to prevent them from developing into full-blown disorders. This can be divided into two different approaches – welfare-driven and risk-driven. The wellness-driven approach focuses on preventing issues before they arise and helping healthy individuals improve their quality of life by maximizing their well-being. On the other hand, a risk-driven approach involves early detection and intervention for at-risk individuals, and reducing long-term effects and preventing recurrence for those who experience serious mental health problems. Preventive psychology combines therapeutic guidance, psychosocial support and resilience-building to promote mental well-being. Preventive psychology is like vaccination for the soul – with resilience, skill-building, social support, etc. acting as antibodies.

Preventive psychology is not an unknown concept – prevention has been researched and discussed since the mid-19th century. It has its roots in the concepts of community psychology – the Swampscott Conference in 1965 marks its origins, in which professionals recognized the limitations of the traditional medical model that focused on individual treatment (Kluss and Karen Grover Duffy, 2012). This led to the realization that the large burden of mental health problems could not be solved by individual treatment; Instead, preventive efforts are needed at the community level. Thus, psychologists were encouraged to consider the larger social and environmental causes of psychological issues rather than focusing solely on their symptoms. Many prevention programs have since been developed, supported by strong empirical and conceptual bases. However, most of the development in this area has occurred in the last decade, and not much progress has been made and/or implemented since then. “The reality is that less than 5% of mental health research funding goes to prevention research, even in countries that invest in prevention” (Arango et al., 2018).

The ignorance and limited application of preventive psychology is regrettable because it has many benefits. The biggest benefit is that it can help reduce the burden on mental health services. There is a huge disparity between the demand and supply of mental health services around the world, with the burden of disorders and issues being too great to be dealt with effectively by the existing mental health force. Thus, if the majority of cases are prevented or individuals are equipped with the tools to self-manage symptoms, the burden will be significantly reduced. Albee (1999) also believes that “no mass disorder has been eliminated by treating one individual at a time” and that only prevention reduces incidence. Furthermore, preventive services are usually cost-effective compared to long-term treatment of chronic conditions. One of the major barriers most people face in seeking therapy is its expensive and time-consuming nature. Thus, why not prevent issues that are both cheap and quick? Research has also found that “savings due to prevention of mental health disorders may be greater than those for other medical conditions” (Arango et al., 2018). Well-being-driven approaches within the field include teaching coping skills and resilience strategies. This will ultimately empower individuals to cope with stress and manage their mental health, thereby promoting long-term well-being. Wellbeing and risk-driven approaches together have the potential to prevent suicide and self-harm. With a suicide rate of 12.4 per 100,000 population in India in 2022, preventive psychology can support the development of effective support networks and self-management strategies to help individuals avoid developing self-harm tendencies (NCRB, 2022). Even in cases where such tendencies emerge, a risk-driven approach can facilitate timely intervention and potentially prevent loss of life due to suicide.

The effectiveness of preventive psychology can be exemplified by the ‘Spark Resilience’ programme, which was implemented in the United Kingdom. Although this was a school-based positive education program, it closely resembles the principles of the wellness-driven approach within preventive psychology. The goal of this program was to promote emotional resilience and related skills and prevent depression, in which children use imaginary situations to explore how their thoughts trigger emotions and behaviors, helping them reflect and learn from the experience. The program was a huge success and was implemented in Japan, Singapore, the Netherlands and beyond. It was found that “students involved in the program had dramatically reduced risks of depression and significantly higher levels of resilience” (Sutton, 2016).

Despite its many benefits, preventive psychology is still not prioritized to tackle the mental health burden. The world is currently facing a global mental health crisis, which is likely to get worse. Globally, 1 in every 8 people lives with a mental disorder, and more than two-thirds of people with mental health conditions do not get the care they need (Schwartz, 2024). India is not far behind, with about 151 million people in a population of 1.4 billion experiencing mental health problems (Data Commons, 2021). In addition to the burden, the country faces a severe shortage of mental health professionals, with only 0.24 licensed clinical psychologists per 100,000 people and a gap of 28% to 83% in treatment of all disorders (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2023; World Health Organization, 2022). Further complicating the problem, only 1% of the total health budget is allocated to mental health, indicating low policy priority (Mahashur, 2024). WHO also predicts that mental health disorders could cost the world $16 trillion by 2030. These worrying statistics highlight the serious burden of mental health issues in India and around the world, underscoring the urgent need for preventive psychology measures to stem the crisis.

If the need is so great why don’t we use it? Several challenges prevent preventive psychology from being widely used to prevent mental health problems. The first is the widespread stigma around mental health in general, which is why people still view therapy as ‘taboo’, let alone consider a therapist when they are not experiencing any problems. People who experience mental health problems are reluctant to seek help because they feel that their problems ‘aren’t that serious.’ Here’s my question – since we don’t wait for high fever to take medicine, why discriminate against our mental health? There is also a lack of awareness regarding mental health, due to which most at-risk individuals do not even know they are at risk or what ‘risk’ is. Most of us consider the risk of a heart attack reasonable, but many will not believe that they need to be protected from suicide or self-harm (Arango et al., 2018). Because of the subjectivity of risk factors and coping mechanisms, standardizing preventive psychology programs is also highly complex. There cannot be one protocol for two people, as they come from different backgrounds, exhibit different personalities and tendencies, and have different genetics – all of which contribute to the development of mental health issues. It is also very difficult to measure the absence of a problem indicating the success of prevention compared to the results of treatment. All these factors need to be addressed by extensive research and testing, with lack of funding and attention towards preventive research acting as a barrier. Short political cycles, fragmented health systems, and bureaucratic inertia also limit the scalability of prevention programs.

How can we develop working preventive psychology programs? The first step is to increase policy and funding support for preventive psychology research to develop strong, evidence-based programs that can be widely implemented. Subsequently, a greater focus on a welfare-driven approach compared to a risk-driven approach would be more widely applicable. Within this, there is a need to expand the association of mental health with just disorders and dysfunction to include well-being and quality of life. The main objective of these efforts should be children and teens Breaking stigma and ensuring early prevention, intervention and resilience building. To ensure maximum efficiency, psychologists should focus on long-term well-being and impart skills such as hardiness, self-esteem, emotional intelligence, problem-solving and social engagement, etc. These skills will ensure self-reliance within individuals and reduce the need for psychologists to actively perform, thereby significantly reducing the burden. However, all these efforts are futile if people are not ready to take preventive efforts for their mental health. Thus, efforts should be made to increase mental health awareness to reduce stigma and normalize receiving therapy without it being a ‘problem’. Because why wait for the ‘big bang’ to start living?

Albee, GW (1999). The only hope is prevention, not cure. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 12(2), 133-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515079908254084

Arango, C., Diaz-Caneza, C.M., McGorry, P.D., Rapoport, J., Sommer, I.E., Vorstman, J.A., McDaid, D., Marin, O., Serrano-Drozdowskij, E., Friedman, R., and Carpenter, W. (2018). Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(7), 591-604. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30057-9

Data Commons. (2021). India – Place Explorer – Data Commons. Datacommons.org. https://datacommons.org/place/country/IND?utm_medium=explore&mprop=count&popt=Person&hl=en

Klus, B., and Karen Grover Duffy. (2012). Community Psychology: Connecting Individuals and Communities. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

NCRB. (2022). ???? ??? ??????? ????? ??? ???????????? ??????? | National Crime Records Bureau. Ncrb.gov.in. https://www.ncrb.gov.in/accidental-deaths-suides-in-india-year-wise.html?year=2022&keyword=

Schwartz, E. (2024, May 20). Global mental health crisis: 10 numbers to pay attention to. Project Hope. https://www.projecthope.org/news-stories/story/the-global-mental-health-crisis-10-numbers-to-note/

Sutton, J. (2016, September 26). 12 Inspiring Examples of Positive Psychology in Real Life. PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/positive-psychology-examples/#looking-at-real-life-examples-of-positive-psychology

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2023). Mental illness: Unstarred question no. 1408, Answered in Rajya Sabha (AU1408). Government of India.

World Health Organization. (2022). Addressing mental health in India. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/364877/9789290210177-eng.pdf?sequence1

Mahashur, S. (2024, March 7). imho blog. Center for Mental Health Law and Policy. https://cmhlp.org/imho/blog/the-interim-union-budget-fy-2024-25-where-does-mental-health-stand/

Moitrayee Das is Assistant Professor at FLAME University, PuneAnd Aparajita Vaid is a psychology graduate and alumnus of FLAME University, Pune.