Two people riding bikes near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco (Photo by Maridav on Shutterstock)

in short

- Exercise shows equivalent effects to antidepressant drugs for depression

- Young adults (18-30) and new mothers see the greatest benefits

- Aerobic exercise and group settings work best

- Depression requires longer programs, anxiety responds to shorter sessions

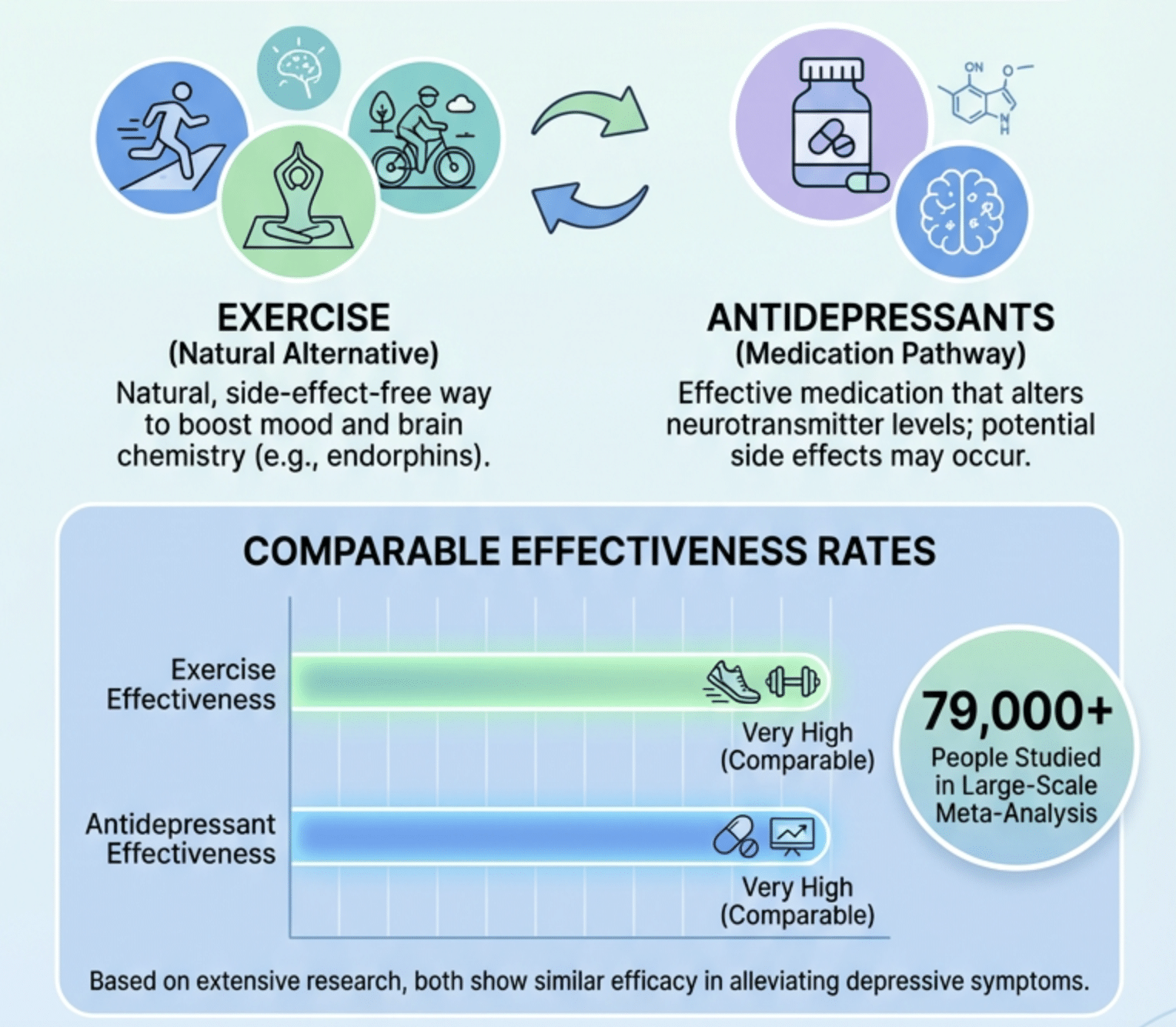

When it comes to depression, running, cycling or even just walking can work just as well as popping a pill. A comprehensive analysis of nearly 80,000 people found that exercise reduced depression symptoms, with effects comparable to, and in some cases even larger than, those commonly reported for antidepressant drugs and psychotherapy in prior research.

The numbers are compelling. Exercise produced an effect size of -0.61 for depression in this review. The authors say this magnitude matches or exceeds the effect sizes of earlier research on antidepressants (-0.36) and psychotherapy (-0.34). Research, published in British Journal of Sports MedicineData from more than 1,000 individual studies spanning children to older adults were examined.

Lead researcher Neil Richard Munro of James Cook University in Australia and his team specifically excluded anyone with chronic physical diseases such as heart disease or cancer. This decision matters because it tells you what the exercise actually does. mental healthWithout the other health problems that muddy the waters.

Groups that benefit most from exercise

The greatest improvements were seen in young adults between the ages of 18 and 30, with exercise producing a particularly strong reduction in symptoms in this age group. This timing matters because depression often first appears at this age.

New mothers also experienced powerful benefits. Postpartum depression hits hard, and finding treatments that work during this sensitive time can seem impossible. Exercise programs designed for postpartum women led to strong reductions in symptoms without the concern of medication during breastfeeding.

What kind of exercise works for depression?

aerobic exercise Came out on top. Running, walking, cycling (activities that get your heart pumping) showed the strongest effects. However, resistance training, yoga, tai chi, and mixed programs also helped. The best exercise is the one you’ll actually do.

Group settings made a real difference. People who exercised with others experienced greater improvements than those who exercised alone. Maybe it’s the accountability, maybe it’s the social connection, maybe it’s just more fun. Whatever the mechanism, working out together seems to add something beyond the physical activity itself.

Supervised programs also outperform unsupervised programs. Having the guidance of a coach or trainer leads to better mental health results than doing your workouts alone.

Depression and anxiety require different exercise plans

Interestingly, depression and anxiety responded differently to exercise prescriptions.

For depression, longer programs worked best: those longer than 24 weeks showed the strongest effects. Medium intensity proved ideal, not too easy but not crushing either. Working out three or more days per week showed a slightly larger reduction than working out once or twice weekly, although both frequencies provided benefits.

Concern told a different story. Shorter programs of eight weeks or less were most strongly associated with reductions in anxiety. Low-intensity exercise showed better results than vigorous activity. More frequent sessions once or twice a week yielded slightly better results than regular sessions, although this conclusion comes from limited reviews.

Those differences mean doctors can no longer just say “do exercise.” Someone with depression may need a consistent, moderate program several times a week. Any paralyzed with anxiety Light movements twice a week may improve performance.

How exercise compares to standard treatments

The comparison of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy needs a closer look. This does not mean that people should stop taking prescribed medications, especially those with severe symptoms or a clinical diagnosis. findings suggest Exercise Needs to be seriously considered as part of treatment, especially for mild to moderate depression.

Exercise provides practical benefits. It is generally low-cost and accessible to most people. Along with improving mood, it also supports physical health. Other research suggests that exercise may work through the same pathways as antidepressants, affecting brain chemicals that regulate mood, as well as potentially aiding new brain cell growth and reducing inflammation.

Beyond biology, there is the psychological element. Setting goals, achieving them, and feeling competent in your body again can change the way depression feels on a day-to-day basis.

Why aren’t doctors prescribing exercise?

Despite solid evidence, exercise is rarely used in clinical practice. Many mental health professionals lack training in exercise prescription and do not feel confident in recommending specific programs. Healthcare systems do not have clear pathways to refer patients to exercise programs, the way they might write prescriptions or refer physicians.

On the patient’s side, starting an exercise routine may seem overwhelming due to depression and anxiety. Lack of motivation, exhaustion, anxiety about the gym or group setting: these create real barriers. Cost and transportation add practical challenges.

Researchers argue that doctors should schedule exercise He has equal faith in traditional treatments also. This means writing specific “prescriptions” stating the type, intensity, duration, and frequency, just like drug instructions. A college student can be successful on an intramural sports team. A new mom may prefer a stroller group with other moms.

The key is to match exercises to suit the individual and their specific mental health needs, then provide them with enough support to really get going.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Anyone considering exercise as a treatment for depression or anxiety should consult their healthcare provider, especially if they have been diagnosed with a mental health condition or are currently receiving treatment.

paper notes

Limitations of the study

This meta-meta-analysis included only English language publications, potentially missing relevant research published in other languages. Different studies defined exercise intensity and duration inconsistently, making accurate comparisons challenging. The research found limited data for some populations, particularly anxiety studies in older adults, youth, and perinatal women. Publication bias analysis suggested some heterogeneity across anxiety studies, indicating that some negative results may not have been published. Most of the included meta-analyses received a low quality rating on the AMSTAR-2 assessment tool, although sensitivity analyzes showed that this did not significantly impact the results.

Funding and Disclosure

The authors declare no specific funding for this research from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The research team reported no competing interests or conflicts of interest related to this study.

Publication details

This research was conducted by Neil Richard Munro, Samantha Teague, Claire Somore, Aaron Simpson, Timothy Budden, Ben Jackson, Amanda Rebar and James Dimock. The study was published in British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2026 with DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2025-110301. Munro is affiliated with James Cook University in Queensland, Australia. The systematic review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020210651) and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Overview of Reviews (PRIOR) framework. For depression, researchers analyzed 57 reviews covering 800 individual studies with 57,930 participants aged 10 to 90 years. For anxiety, they examined 24 reviews that included 258 studies with 19,368 participants ages 18 to 67.